Sperm Fascination

It all started in biology class. Sitting in front of our microscopes looking at fly legs, onion skin, dyed potato slices and other pieces of flora. Exciting right? Nooooooope! No idea what else someone would use a microscope for… Of course! Observing paramecium in a puddle of water – finally we get to where the action’s at!

I had always wanted my very own microscope. Not one for kids though. A proper one, so to speak. As the motto goes “my house, my car, my microscope”. It always bothered me that, when using the simpler ones, I had to close one eye.

I found my microscope in a catalogue at the optometrist (we didn’t have internet shopping back then) – binocular, with additional accessories like a second eyepiece set for higher magnification, a cross table, a micrometer scale, a hand microtome and a staining kit. As with all new things, that are unbelievably amazing at first, it eventually ended up in the most remote corner of a cupboard – I never imagined I would actually need to use the set. So years later, when I came up with the idea for the contraceptive valve, it suddenly became an important tool.

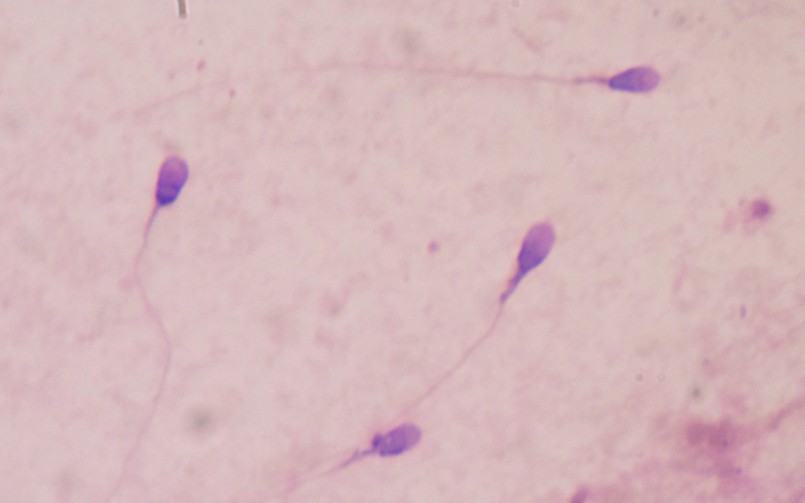

Sperm cells in motion

Watching sperm cells under a microscope is fascinating. There are those in a bit of a rush travelling at full speed, as well as others that just swim around in a circle as though they’re lost. There are also dead sperm cells or cell fragments. According to literature a certain percentage of sperm cell scraps is actually quite normal.

I always find it really fascinating, what sperm cells get up to. I recommend that potential volunteers, for the medical trials, take a look as well. A simple school microscope with 400x to 600x magnifying power will work just fine and, thanks to wikipedia, there are also simpler ways to get information on sperm cells.

The basics of sperm-cell-watching

Nevertheless, for those who would also like to know how sperm count is calculated, here are the basics. Professional laboratories use a Neubauer-counting chamber (or hemocytometer), in which a certain amount of sperm cells is inserted and counted. My method, however, requires a digital micrometer screw gauge. First, adjust the microscope’s field of view to a magnification of 400. My microscope, for example, has a 400x magnification at a 0.45mm field diameter and a 600x magnification at 0.31mm.

Those who do not have a micrometer scale can lay a thin pin under the microscope after determining the correct diameter with the micrometer screw gauge. The clearly visible thickness of the pin will aid in estimating the correct viewing diameter.

Next, put a glass coverslip on a normal slide and measure the total thickness with the digital micrometer screw gauge. If the digital display can be adjusted to 0, there is no need to worry about the degree. Remove the glass coverslip, place one small drop of liquified (15 to 30 minute waiting time), well-stirred semen in the middle of the slide and place the glass coverslip on top.

This set-up goes between the micrometer screw gauge. Turn the micrometer screw to press the glass coverslip and slide against each other, but only until a remaining value of 0.020mm or 20µm is reached on the display. Clean away any liquid that leaks out laterally, otherwise there’ll be a bit of a mess. The diameter of the head of a sperm cell is about 3µm, with a space of 20µm between the glass coverslip and slide the sperm cells have enough room to move freely.

View through the microscope

Now we finally have everything under the microscope, where the entire cylindrical volume (view of circular surface x 0,02 mm) is completely visible. Next, count and make a projection for 1 ml (cm³) or for the entire volume of the semen. If the amounts are difficult to determine, because of constant movement, choose – if possible – a higher magnification or buy a microscope with a USB camera with video and photo functions. These have been available since 2007 for 50€ at major stores and don’t really cost an arm and a leg.

Clemens Bimek wishes you good luck with your experiments

Photo: stained sperm sample under a light microscope